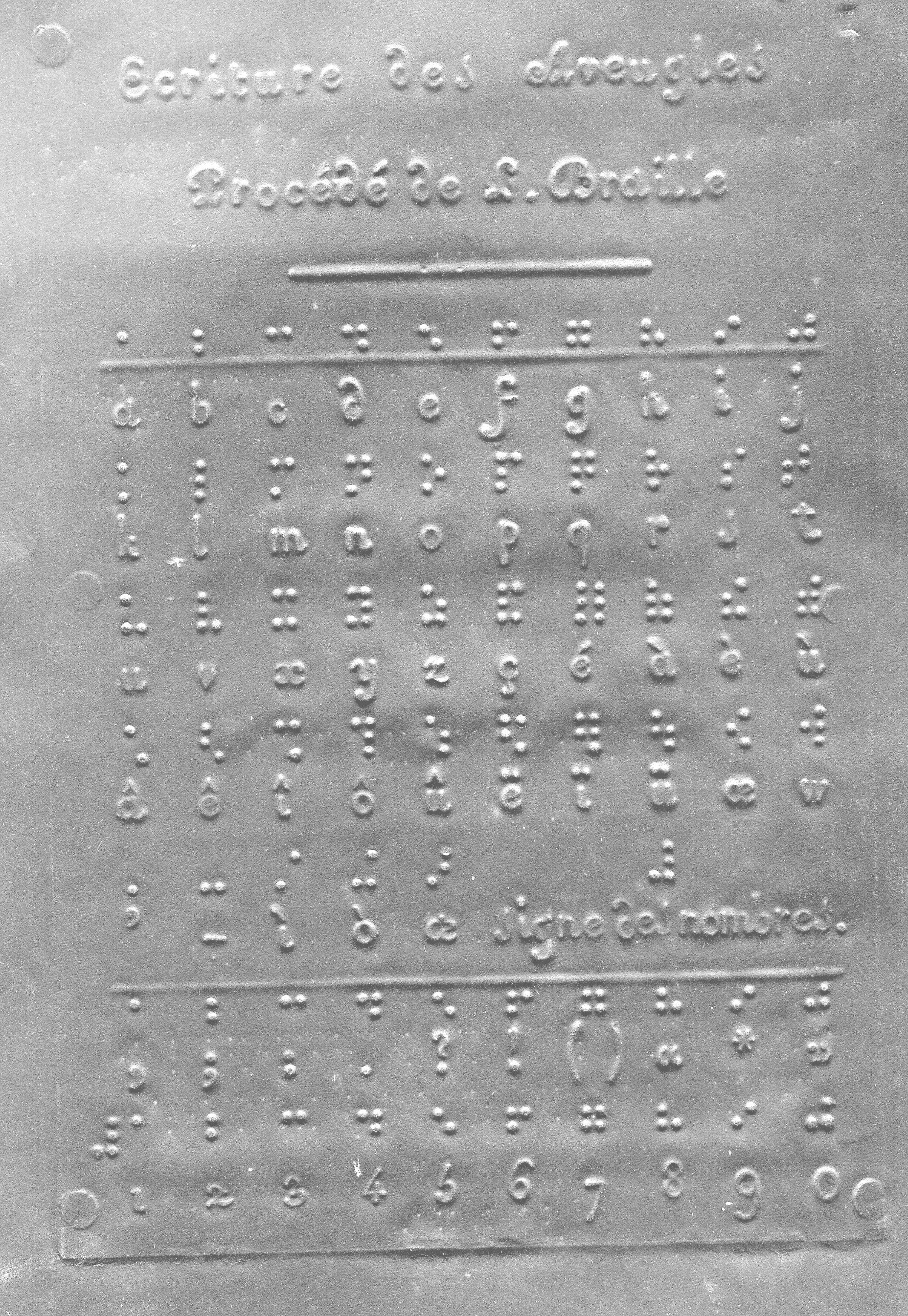

So it was at the very young age of 12 that Louis Braille, together with the other pupils, tried the system invented by Captain Charles Barbier de la Serre, which made him create his own alphabet. However, in a world run by sighted people, his system wasn't accepted, and teaching by means of books and black writing, which remained the reference at the time, continued for another twenty years.

So it was at the very young age of 12 that Louis Braille, together with the other pupils, tried the system invented by Captain Charles Barbier de la Serre, which made him create his own alphabet. However, in a world run by sighted people, his system wasn't accepted, and teaching by means of books and black writing, which remained the reference at the time, continued for another twenty years.

1878, a watershed year

A major turning point took place in 1878: at the World Congress for the Improvement of the Fate of the Blind and Deaf-Mute People held in Paris. After lengthy discussions, the Braille system was recommended as a frame of reference for all countries. It was only a recommendation at the time, and then became fully accepted and widespread at the turn of the century. After the Second World War, UNESCO (the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) steered the efforts to unify Braille in India and then for all Arabic languages. Subsequently, other unifications and adaptations for languages such as French, Spanish, and English, spoken in many countries, followed. Today, virtually every language has its own version of Braille.

Grateful nation

By the end of the 19th century, Louis Braille's recognition came.

The town of Coupvray first gave him a permanent resting place in 1885, then a monument in 1887. In 1950, a UNESCO delegation visited his grave.

In 1951, associations of blind people raised the idea of relocating Louis Braille to the Panthéon. That year in July, the association The Friends of Louis Braille (Les amis de Louis Braille) was founded to acquire his childhood home where he was born and raised and turn it into a museum.

In 1952, both projects came to fruition: Louis Braille was transferred to the Panthéon on June 21, 1952, excluding his hands which were kept in the cemetery as relics. In October 1952, his house was bought by the association. It was first opened to the public in 1953 and was officially inaugurated in 1954.