The National Institute for Blind Youth (Institut national des jeunes aveugles, INJA), created in 1785 and Louis Braille’s second home, owes its existence to Valentin Haüy, a scholar who was dedicated from early on to the welfare of blind and visually impaired people.

The National Institute for Blind Youth (Institut national des jeunes aveugles, INJA), created in 1785 and Louis Braille’s second home, owes its existence to Valentin Haüy, a scholar who was dedicated from early on to the welfare of blind and visually impaired people.

Its pupils were taught the same subjects as in traditional schools as well as music and an array of manual trades, to ensure their autonomy after leaving the Institute.

Despite its modest start, with only a dozen pupils, the Institute was a significant milestone, because it was the very first time blind children’s formal education had been envisaged.

An eventful history

The Institute’s status changed during the French Revolution. Previously financed by the independent Société Philanthropique, the Institute was nationalized by decree in 1791, and became a part of the Institute for Deaf-Mutes (Institution Nationale des Sourds-Muets).

It regained its autonomy in 1794, when it became the National Institute for the Working Blind (Institut national des aveugles travailleurs). But in 1800, the Institute was affiliated to the Quinze-Vingts Hospital (Hospice des Quinze-Vingts).

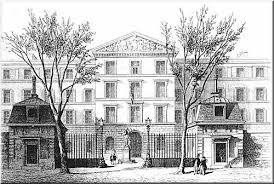

In 1816, it regained its independence. Renamed the Royal Institute for Blind Youth (Institution Royale des Jeunes Aveugles), it moved to Rue Saint Victor (now Rue des Écoles), in the premises of the former Collège des Bons-Enfants. This is where Louis Braille became first a pupil and then a teacher. But the premises were insalubrious and many pupils developed tuberculosis, which prompted the State to build new, structurally sound buildings. Not until 1838, however, was a law passed to that effect. In 1843, new buildings were constructed at 56 Boulevard des Invalides, which is where the INJA is still located today.

Three successive directors

Three successive directors left their mark on the Institute.

The first, Sébastien Guillié, was previously a military doctor and eye doctor. Known for being strict, he significantly contributed to improving music education.

His successor, in 1821, was Alexandre-René Pignier, a former physician at the Séminaire Saint-Sulpice, who attempted to move the Institution because of the buildings' insalubrity. Another notable fact is that he gave Louis Braille decisive support by publishing two editions of his alphabet system, as well as the first book written in Braille in 1837.

The last director was Pierre-Armand Dufau. Opposed to Alexandre-René Pignier, Dufau ensured his forced departure in 1840. Averse to Braille, he had it banned, but the students continued to use it in secret. Eventually however, Dufau recognized its value, in particular thanks to his assistant Joseph Guadet’s action. For the inauguration of the new premises in 1844, reading and writing demonstrations were organized to show the system's superiority.